What did our ancestors think when they looked up at the night sky? All cultures ascribed special meaning to the Sun and the Moon, but what about the pearly band of light and shadow we call the Milky Way?

My recent study showed an intriguing link between an Egyptian goddess and the Milky Way.

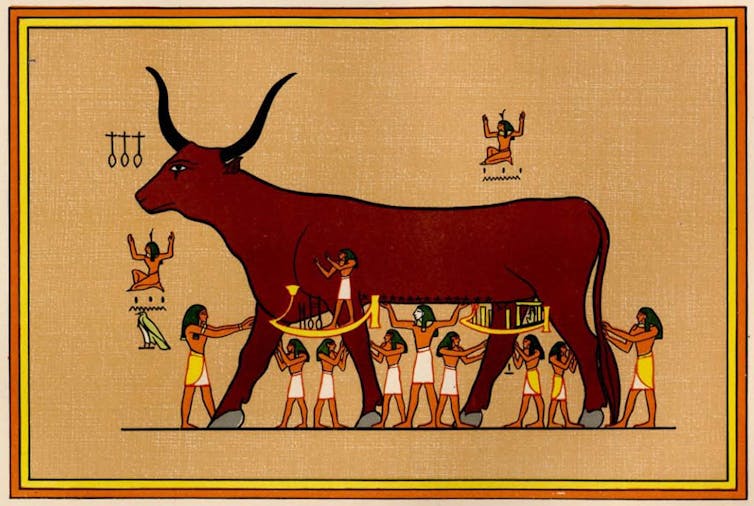

Slowly, scholars are putting together a picture of Egyptian astronomy. The god Sah has been linked to stars in the Orion constellation, while the goddess Sopdet has been linked to the star Sirius. Where we see a plough (or the big dipper), the Egyptians saw the foreleg of a bull. But the Milky Way’s Egyptian name and its relation to Egyptian culture have long been a mystery.

Several scholars have suggested that the Milky Way was linked to Nut, the Egyptian goddess of the sky who swallowed the Sun as it set and gave birth to it once more as it rose the next day. But their attempts to map different parts of Nut’s body onto sections of the Milky Way were inconsistent with each other and didn’t match the ancient Egyptian texts.

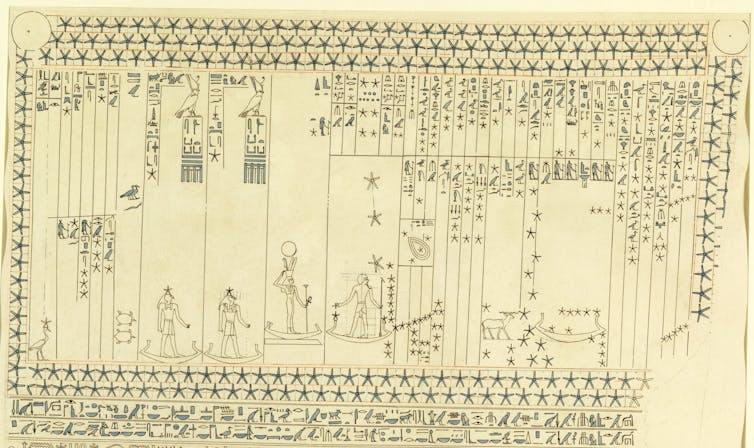

In a paper published in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, I compared descriptions of the goddess in the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and the Book of Nut to simulations of the Milky Way’s appearance in the ancient Egyptian night sky.

Carved onto the walls of the pyramids more than 4,000 years ago, the Pyramid Texts are a collection of spells to aid the kings’ journey to the afterlife. Painted on coffins a few hundred years after the age of the pyramids, the Coffin Texts were a similar collection of spells. The Book of Nut described Nut’s role in the solar cycle. It has been found in several monuments and papyri, and its oldest version dates back some 3,000 years ago.

The Book of Nut described Nut’s head and groin as the western and eastern horizons, respectively. It also described how she swallowed not only the Sun but also a series of so-called “decanal” stars that are thought to have been used to tell time during the night.

From this description, I concluded that Nut’s head and groin had to be locked to the horizons so that she could give birth and later swallow the decanal stars as they rose and set throughout the night. This meant that she could never be mapped directly onto the Milky Way, whose different sections rise and set as well.

I did, however, find a possible link to the Milky Way in the orientation of Nut’s arms. The Book of Nut describes Nut’s right arm as lying in the northwest and her left arm in the southeast at a 45 degree angle to her body. My simulations of the Egyptian night sky using the planetarium software Cartes du Ciel and Stellarium revealed that this orientation was precisely that of the Milky Way during the winter in ancient Egypt.

The Milky Way is not a physical manifestation of Nut. Instead, it may have been used as a figurative way to highlight Nut’s presence as the sky.

During the winter, it showed Nut’s arms. In the summer (when its orientation flips by 90 degrees) the Milky Way sketched out her backbone. Nut is often portrayed in tomb murals and funerary papyri as a naked, arched woman, a portrayal that resembles the arch of the Milky Way.

However, Nut is also portrayed in ancient texts as a cow, a hippopotamus and a vulture, thought to highlight her motherly attributes. Along the same lines, the Milky Way could be thought of as highlighting Nut’s celestial attributes.

The ancient Egyptian texts also describe Nut as a ladder or as reaching out her arms to help guide the deceased up to the sky on their way to the afterlife. Many cultures around the world, such as the Lakota and Pawnee in North America and the Quiché Maya in Central America, see the Milky Way as a spirits’ road.

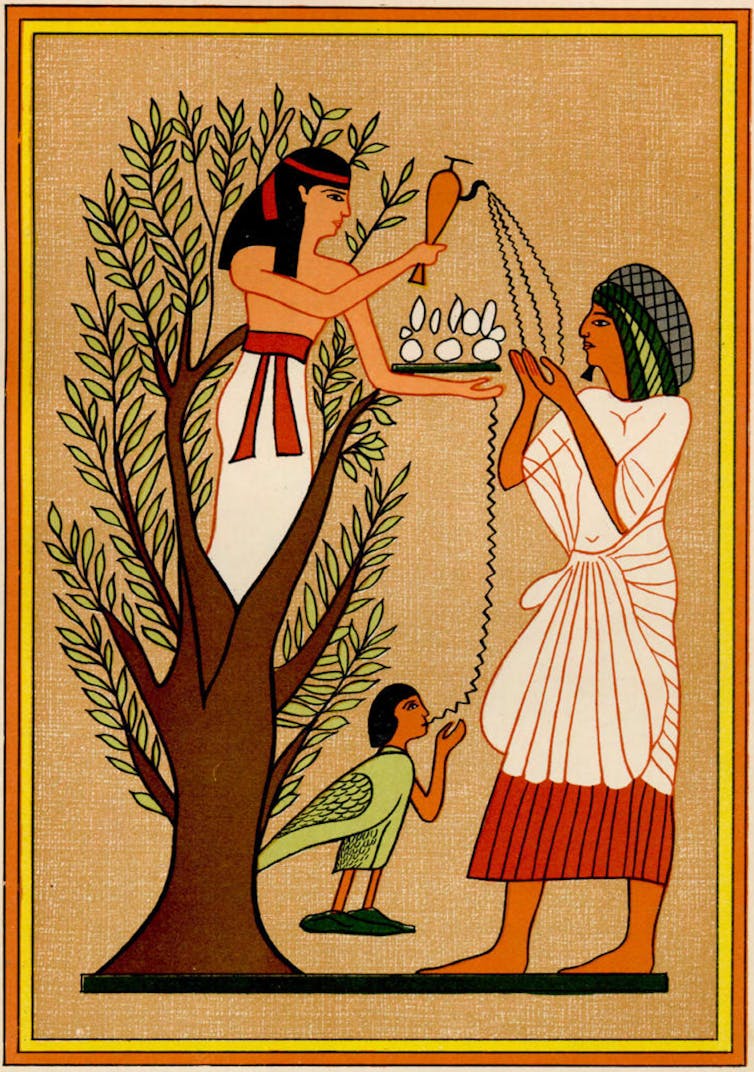

The Book of Nut also describes the annual bird migration into Egypt and ties it both to the netherworld and to Nut. This section of the Book of Nut describes Ba birds flying into Egypt from Nut’s northeast and northwest sides before turning into regular birds to feed in Egypt’s marshes. The Egyptians considered the Ba, portrayed as a human-headed bird, to be the aspect of a person that imbued it with individuality (similar, but not identical, to the modern Western concept of the “soul”).

The Bas of the dead were free to leave and return to the netherworld as they wished. Nut is often shown standing in a sycamore tree and providing food and water to the deceased and their Ba.

Once again, several cultures across the Baltics and northern Europe (including the Finns, Lithuanians, and Sámi) view the Milky Way as the path along which birds migrate before winter. While these links don’t prove a connection between Nut and the Milky Way, they show that such a connection would place Nut comfortably within the global mythology of the Milky Way.